Emma reviews Chaim Potok’s novel, I Am The Clay, and ponders how a good story can help us see more clearly one another’s lives.

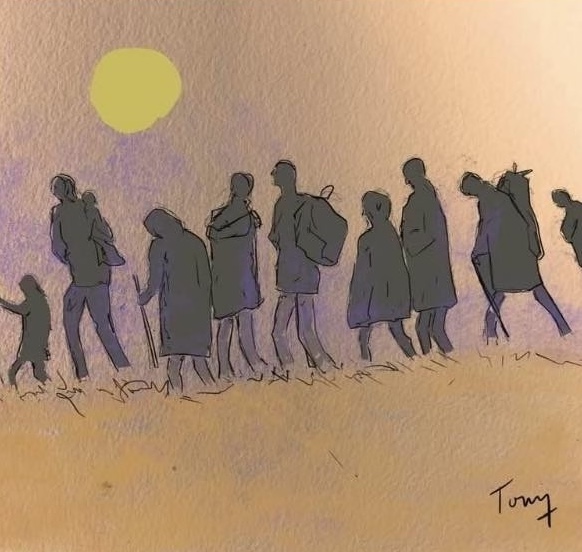

Set in 1950s Korea, Chaim Potok’s I am the Clay evokes an experience of frigid desolation as ordinary people are forced to flee for fear of slaughter. When Chinese troops move through Korea, an old man and his wife struggle to survive. Their wandering is made more complicated when they rescue a boy, badly injured and on the cusp of death. The trio’s endless walking, trudging through ice and snow, leaves readers feeling hollow and disorientated, emotionally mirroring the experience of these characters.

I read a review that criticised Potok’s book as tedious, monotonous and dull. In addition to showcasing limited empathetic powers, this criticism inadvertently points to the precise strength of this narrative – here readers are given a brief experience of displacement without any of the distress or discomfort people actually have to endure in such situations.

As I read this book, my thoughts branched in various directions.

Firstly, the power of literature is that we are provided with opportunities to experience situations and encounters which most of us will never face in reality. As Niall Williams puts it in his novel This is Happiness, the best of books catch an echo of life, leaving you enriched and with the sense that ‘you have been in the company of something alive that has caused you to realised once again how astonishing life is, and you leave the book…with that illumination, which feels….holy… [a] human raptness’. Traversing imaginative landscapes, therefore, brings about a substantive difference in our lives, broadening our experience and building our powers of empathy.

Potok’s narrative does precisely this but in a deeply troubling way through its visceral rawness. The travellers’ continuation, placing one foot in front of the other despite overwhelming hopelessness, is almost hypnotic. We want to look away but can’t. Their weary exhaustion is felt by us as we become emotionally spent through merely witnessing their dogged endurance. One of the most horrifying moments is when the black cloud boiled up yet again over the plain, expanding to fill every crevice, from the fabric of their clothes to the tastebuds on their tongues. When we discover this pollutant is the ultimate harbinger of death, the consequence of having to dispose of the mounting bodies that can’t be buried beneath the thick layers of ice, the brutal reality and vulnerability of these refugees haunts us utterly.

Of course, such stories are not limited to the fictional realm. They come out of reality. For Potok it was his experience serving in South Korea in a US front-line medical battalion and engineer combat battalion. With scenes of war playing out on our phone screens on a daily basis, we are a little more aware of the experience of displaced people today than we might have been 15 years ago. With no names, Potok’s fictional characters invite us to read their story as standing for the lives of so many in reality. Both the war in Ukraine and the conflict in Gaza feature more familiar landscapes which are helping us to make that imaginative leap into the lives of people fleeing for fear of death. But these reported stories are only some of the many places under siege today.

Since leaving teaching and moving into a new sphere of work, I am learning about the lives of people who never make it onto our news feeds. The ongoing conflict in DR Congo and South Sudan are but two examples of places I knew little about until 18 months ago.

As a consequence, in this next phase of my working life I am appreciating this idea of experiential reading in another way. Working alongside displaced people and refugees who are living in vastly different circumstances to my own, I am seeking ways to understand. But books like Potok’s are not simply helping me imagine what others are having to endure. No, Potok’s book has a more important role than that. It helps prevent a reduction of the individual, a two-dimensional interpretation of the life of another. I found the messy characterisation of Potok’s ‘old man’ a sobering reminder of the flawed nature of every human being. At the same time, there was much to celebrate in the elevation of the ‘old woman’ as someone freed from cultural constraint in the levelling situation of displacement. To see her discover a voice, challenge patriarchy, reach out beyond what was socially acceptable in order to help the boy – all these things speak to the strength within human beings, of our inherent worth as people, our tremendous capacity to survive adversity and our ability to alter the present for good.

Faceless numbers are used to fuel fear of those seeking shelter on our shores. I have found it salutary to know the names and faces of those we work with, all of whom are filled with dignity, complexity and roundedness, just like every other person I know. To learn about the joys and struggles of those forced to flee their homes helps prevent people being reduced to statistics. But, when we don’t know actual individuals, books like I am the Clay, certainly go a long way to helping pave the path of empathetic understanding.

This month I am beginning the task of putting together CMS Ireland’s next children’s resource. With a focus on displaced people and refugees, I am very grateful to have read Potok’s book as another avenue for personal learning. I hope that the materials we put together will go some way towards helping children look out beyond the immediate parameters of their own lives to the lives of others.

Featured image by Tony McGall.